Enduring Powers of Attorney: A Complete Guide to Securing Your Future

Understand enduring powers of attorney: define, create, and manage your financial & personal care decisions. Secure your future today.

What is an Enduring Power of Attorney? A Foundational Overview

Life is unpredictable. We all hope to remain in control of our decisions, but unforeseen circumstances can change that. Planning for such a possibility is not about anticipating the worst. It is about empowering ourselves and protecting our loved ones.

This guide will explore the enduring power of attorney (EPA). We will dig into what an EPA is, its historical roots, and how it safeguards our autonomy. We’ll also examine the legal nuances across different regions and the critical steps involved in securing customized enduring powers plans that truly reflect our wishes and protect our future.

We believe everyone deserves peace of mind. Understanding enduring powers of attorney is a key step towards achieving it.

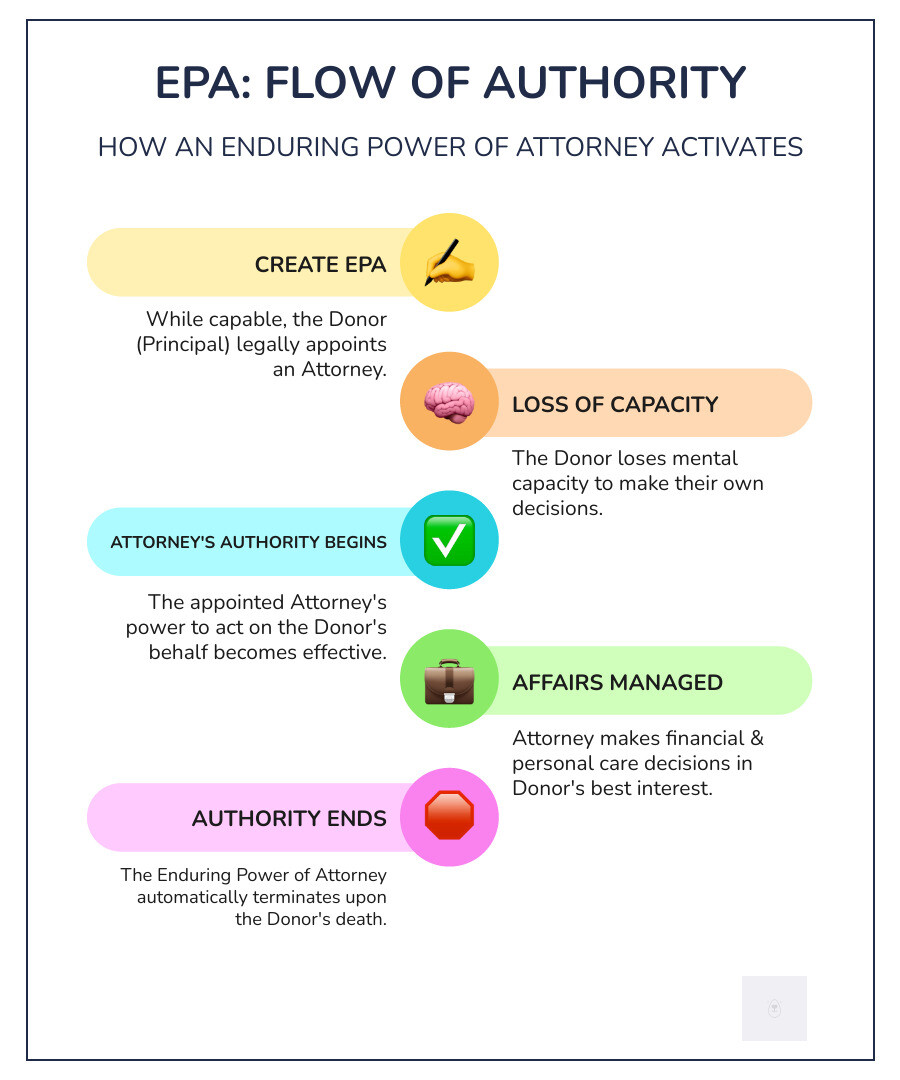

An Enduring Power of Attorney (EPA) is a crucial legal document that allows an individual, known as the “donor” or “principal,” to appoint another person, referred to as the “attorney,” to make decisions on their behalf. What sets an EPA apart from a standard or general power of attorney is its “enduring” quality: it remains valid and effective even if the donor loses mental capacity. This continuing authority is paramount for ensuring that your affairs are managed according to your wishes, should you become unable to make those decisions yourself.

In contrast, a general power of attorney typically ceases to be effective when the donor loses mental capacity. This distinction is vital for long-term planning, as the primary purpose of an EPA is to provide a safety net for future incapacity.

An EPA can cover a broad spectrum of decisions in two main categories: financial affairs and personal care decisions.

- Financial Affairs and Property Management: This aspect of an EPA grants the attorney the authority to manage your money, property, and other assets. This can include paying bills, managing bank accounts, collecting income, dealing with investments, and even buying or selling real estate on your behalf.

- Personal Care and Healthcare Choices: In many jurisdictions, an EPA (or a similar document) can also extend to personal care matters. This allows your attorney to make decisions about your daily living, such as where you live, what you eat, your clothing, and your social activities. Crucially, it can also encompass healthcare decisions, including consenting to or refusing medical treatment.

Entrusting these critical decisions to someone you trust, even when you can no longer articulate your wishes, offers immense peace of mind. It ensures continuity in managing your life and upholds your autonomy through the actions of your chosen representative.

The Scope of an Attorney’s Authority

The legal authority granted to an attorney under an EPA is extensive, mirroring many of the powers the donor would possess if they retained full capacity. This authority typically includes:

- Paying bills: Ensuring all financial obligations, from utilities to mortgages, are met.

- Managing investments: Overseeing portfolios, buying or selling stocks, and making financial decisions to protect and grow assets.

- Selling property: Handling the sale of real estate or other significant assets if necessary, for example, to fund care.

- Signing legal documents: Executing contracts, deeds, and other legal papers on your behalf.

- Making healthcare decisions: Consenting to or refusing medical treatments, in line with your known wishes or best interests.

- Choosing living arrangements: Deciding on suitable accommodation, such as a care home, if you are no longer able to live independently.

While the attorney’s powers are broad, they are not limitless. Their overarching duty is to act in your best interests, a principle we will explore further.

What an Attorney Cannot Do

Despite the wide-ranging powers, an attorney acting under an EPA has specific limitations to prevent misuse and protect the donor’s fundamental rights. Generally, an attorney cannot:

- Make or change a Will: A Will is a personal document that reflects your wishes for your estate after your death. An attorney cannot alter this.

- Grant a new Power of Attorney: The authority granted is personal to the attorney and cannot be delegated by them to someone else via a new POA.

- Change beneficiaries on life insurance or pension plans: These are typically personal decisions with long-term financial implications.

- Make substantial gifts: While an attorney can usually make customary or reasonable gifts (e.g., birthday or Christmas presents from your estate), they cannot make large, unusual gifts that would significantly deplete your assets, unless explicitly authorized in the EPA or by court order.

- Vote on your behalf: Political decisions remain personal and are not covered by an EPA.

- Act against your best interests: This is the cornerstone of an attorney’s duty. Any action taken must be for your benefit and in line with your known wishes, values, and beliefs.

Understanding the scope and limitations of an attorney’s power is crucial for both the donor and the appointed attorney. This ensures that the EPA functions as intended—as a tool for protection, not exploitation.

The Legal Landscape: How EPAs Vary by Jurisdiction

An enduring power of attorney, or its equivalent, is rooted in common law principles, but its specific implementation and terminology can vary significantly across different jurisdictions. While the core idea remains consistent—appointing someone to manage your affairs if you lose mental capacity—the legal frameworks, requirements, and even the names of the documents differ.

The Shift in English Law: From EPA to LPA

In English law, the Enduring Powers of Attorney Act 1985 established enduring powers of attorney (EPAs). These documents allowed individuals to appoint an attorney to manage their property and financial affairs, with the authority continuing even if they lost mental capacity. However, a key limitation of EPAs was their inability to cover health and welfare decisions. They also operated on a somewhat binary view of mental capacity, struggling with concepts of fluctuating or partial capacity.

The Law Commission highlighted these issues in their 1995 report on ‘Mental Incapacity’ Mental Incapacity Mental Incapacity(PDF)(Report). The Law Commission, 28 February 1995, recommended significant reforms. This led to the introduction of the Mental Capacity Act 2005, which came into force on October 1, 2007. This Act replaced EPAs with a new system: Lasting Powers of Attorney (LPAs).

LPAs are more comprehensive, allowing for two distinct types:

- Property and Financial Affairs LPA: Similar to the old EPA, covering money and property.

- Health and Welfare LPA: A new addition that covers decisions about medical treatment, daily routine, and care arrangements.

A critical point for many is the validity of older documents: EPAs signed before October 1, 2007, remain valid and can still be used. However, new EPAs cannot be created. When a donor with an existing EPA begins to lose mental capacity, the EPA must be registered with the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) for the attorney to continue acting legally. This registration process ensures oversight and protection. For more details on acting as an attorney under an EPA in the UK, resources like Direct.Gov – Enduring power of attorney, and Acting as an attorney provide valuable guidance. The Mental Capacity Act 2005, Schedule 4, outlines the legal framework for these documents.

Navigating Canadian Provincial Laws

Canada, with its provincial and territorial legal systems, presents a diverse landscape for enduring powers of attorney. While the federal government offers general information (e.g., Government of Canada on Powers of Attorney), provincial legislation governs the specifics.

- Ontario: Here, the relevant documents are the “Continuing Power of Attorney for Property” (CPOA) and the “Power of Attorney for Personal Care” (POAPC). A CPOA allows an attorney to manage financial affairs and continues if you become mentally incapable. A POAPC grants authority over personal care decisions, including healthcare. To make a CPOA, you must be at least 18 years old and mentally capable; for a POAPC, you must be at least 16. Ontario law typically requires two witnesses. Resources like the Power of Attorney Q&A brochure from the Office of the Public Guardian and Trustee provide extensive information.

- Alberta: Alberta uses the term “Enduring Power of Attorney,” which is defined by the Powers of Attorney Act. This document allows an attorney to make financial decisions on your behalf and can be effective immediately or only upon loss of capacity. If you lose capacity without an EPA, family members may need to go to court to become a trustee, which is a time-consuming and costly process.

- New Brunswick: The “Enduring Powers of Attorney Act” in New Brunswick, which became law on July 1, 2020, streamlines the legislation. It also allows appointing a ‘monitor’ to oversee the attorney’s conduct. For property-related EPAs, a New Brunswick lawyer must witness the signing. The Public Legal Education and Information Service of New Brunswick (PLEIS) offers further details.

The table below provides a simplified comparison of key features across these jurisdictions:

Feature England (LPA) Ontario (CPOA/POAPC) Alberta (EPA) New Brunswick (EPA) Document Name Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) Continuing POA for Property (CPOA), POA for Personal Care (POAPC) Enduring Power of Attorney (EPA) Enduring Power of Attorney (EPA) Types Property & Financial Affairs; Health & Welfare Property; Personal Care Financial (can include personal care if specified) Property; Personal Care Witness Requirements 2 witnesses, Certificate Provider 2 witnesses (specific exclusions) Varies, often 1-2 witnesses Property: NB Lawyer; Personal Care: 2 adult witnesses Registration Mandatory with OPG when capacity lost Not required (recommended for financial institutions) Not required (recommended for financial institutions) Not required (unless for land transactions) Age to Create (Min) 18 Property: 18; Personal Care: 16 18 19 Effective upon Incapacity Yes Yes Yes Yes Replaced EPAs Yes, in 2007 No direct replacement, evolved No direct replacement, evolved New Act in 2020, but not a replacement of concept This jurisdictional diversity underscores the importance of understanding the specific laws in your region when creating an enduring power of attorney.

Creating and Implementing Your Estate Planning Enduring Powers

The process of creating an EPA is a significant step in comprehensive estate planning. It involves careful consideration of legal requirements, personal preferences, and the trustworthiness of your chosen attorney.

Eligibility and Capacity Requirements

To create a legally valid EPA, you, as the donor, must meet specific eligibility criteria, primarily concerning age and mental capacity:

- Age: You must be of legal age to grant a power of attorney. This is typically 18 years old for property-related matters, though some jurisdictions, like Ontario, allow individuals as young as 16 to create a Power of Attorney for Personal Care.

- Mental Capacity: This is the most crucial requirement. You must have the mental capacity to understand the nature and effect of the document you are signing. This means you must:

- Understand the powers you are giving to your attorney.

- Appreciate when these powers can be exercised (e.g., immediately or upon loss of capacity).

- Know that you can revoke the EPA while you still have capacity.

- Understand that the powers will continue or commence if you lose decision-making capacity.

- Appreciate the potential consequences of granting such authority, including the risk of misuse.

The concept of ‘mental capacity’ is not always straightforward. It’s often assessed on a decision-by-decision basis; a person might have capacity for some decisions but not others. If there’s any doubt about your capacity, a medical assessment may be required to ensure the EPA’s validity and to protect against future challenges.

Choosing Your Attorney

Selecting the right person (or people) to be your attorney is perhaps the most critical decision in the entire process. This individual will hold significant power over your life and assets, so trust is paramount. Considerations for choosing an attorney include:

- Trustworthiness: This is non-negotiable. Your attorney must be someone you implicitly trust to act honestly and in your best interests.

- Financial acumen: For a property EPA, your attorney should have a good understanding of financial matters, or at least be capable of seeking professional advice.

- Willingness to act: The role of an attorney can be demanding. Ensure your chosen individual is willing and able to take on this responsibility.

- Availability and reliability: They should be accessible and dependable, especially if urgent decisions are required.

- Appointing alternates: It’s wise to name one or more alternate attorneys in case your primary choice becomes unable or unwilling to act.

- Joint vs. several attorneys: If you appoint multiple attorneys, you must specify whether they must act “jointly” (all agree on every decision) or “jointly and severally” (any one of them can make decisions independently). “Jointly and severally” offers more flexibility but requires careful consideration of potential disagreements.

The Role of a Lawyer in Estate Planning: Enduring Powers

While some jurisdictions offer DIY kits for creating powers of attorney, engaging a lawyer is highly recommended, especially for enduring powers. A legal professional can provide invaluable assistance by:

- Avoiding legal pitfalls: Ensuring the document is legally sound, properly executed, and compliant with your specific jurisdictional requirements.

- Ensuring validity: A lawyer can help confirm you meet the capacity requirements and properly witness the document, reducing the likelihood of future challenges.

- Tailoring the document to specific needs: Your EPA can be customized to include specific instructions, limitations, or conditions that reflect your unique circumstances and wishes.

- Explaining legal duties: A lawyer can fully inform your chosen attorney about their legal responsibilities and fiduciary duties.

- Navigating complex family or business situations: If you have a complex family dynamic, substantial assets, or a business, a lawyer can help structure your EPA to prevent disputes and ensure smooth management.

For those seeking to ensure their plans are robust and personalized, consulting with legal experts to create customized enduring powers plans is an essential step. They can help you understand the nuances of the law and craft a document that truly serves your long-term interests.

Navigating the Lifecycle of an EPA: Risks, Revocation, and Responsibilities

Once an Enduring Power of Attorney is in place, its lifecycle involves ongoing responsibilities for the attorney, potential risks, and mechanisms for revocation or amendment. Understanding these aspects is crucial for both the donor and the attorney.

Key Considerations for Your Estate Planning Enduring Powers

Attorney Duties and Responsibilities: An attorney acting under an EPA holds a significant position of trust and carries stringent legal and ethical duties. These include:

- Fiduciary responsibility: The attorney must act solely in the donor’s best interests, putting the donor’s needs above their own.

- Acting in best interest: This means making decisions that the donor would have made if they had capacity, considering their past wishes, beliefs, and values.

- Record keeping: Attorneys for property must maintain meticulous records of all financial transactions, including income, expenses, and asset management. This transparency is vital for accountability.

- Avoiding conflicts of interest: An attorney must not use their position to benefit themselves or others at the donor’s expense. For example, they generally cannot sell the donor’s property to themselves or a family member at below market value.

- Consultation: Where possible, the attorney should consult with the donor and any other relevant individuals named in the EPA (e.g., family members, medical professionals).

These duties are similar to those of an executor, who manages an estate after death. Just as we explored in “What Does an Executor Do?”, the attorney’s role is one of diligent stewardship.

Advantages of an EPA: The benefits of having an EPA are profound:

- Preserves autonomy: It allows you to choose who will decide for you, rather than a court.

- Avoids court intervention: Without an EPA, if you lose capacity, your family may have to apply to the courts for guardianship or trusteeship, a process that can be costly, time-consuming, and emotionally draining.

- Ensures continuity: Your affairs can continue to be managed seamlessly without interruption.

- Reduces family stress: Your loved ones are spared the burden of making difficult decisions without legal authority or having to steer complex court procedures.

Risks and Consequences of Not Having an EPA: While advantageous, EPAs are not without risks, primarily if the attorney is untrustworthy.

- Risks of financial abuse or mismanagement: Unfortunately, there is always a risk that an attorney might abuse their power, mismanage funds, or act fraudulently. This is why choosing a trustworthy individual is paramount.

- Consequences of not having an EPA: If you lose mental capacity without an EPA, the consequences can be severe. Your family will likely have to apply to a court to appoint a guardian or trustee to manage your affairs. This can lead to:

- Loss of control: The court may appoint someone you would not have chosen.

- Delays and expense: Court applications are often lengthy and incur significant legal fees.

- Family disputes: Disagreements can arise among family members over who should be appointed.

Joint Bank Accounts vs. EPAs: Some people consider joint bank accounts an alternative for financial management, especially for older individuals. However, as highlighted in resources like “What every older Canadian should know about: Powers of attorney (for financial matters and property) and joint bank accounts”, joint accounts come with significant risks:

- Loss of control: Any joint account holder can withdraw all funds without the other’s consent.

- Creditor claims: The money in a joint account can be vulnerable to the creditors of any account holder.

- Inheritance disputes: Upon death, the “right of survivorship” often means the surviving joint holder inherits the funds, which can contradict a Will and lead to family disputes.

- Lack of accountability: Unlike an attorney, a joint account holder has no fiduciary duty to act in your best interest or keep records.

An EPA offers far greater protection, accountability, and control over your assets than a joint bank account.

Revoking or Amending an EPA

Life circumstances change, and so might your wishes or your choice of attorney. Therefore, understand how to revoke or amend an EPA:

- Revocation process: You can revoke your EPA at any time as long as you have the mental capacity to do so. This typically requires a written statement of revocation, signed and witnessed, as the original EPA was executed.

- Mental capacity requirement: You must possess the necessary mental capacity to understand that you are canceling the document and its implications.

- Notifying the attorney and institutions: Once revoked, you must immediately notify your attorney in writing and retrieve all copies of the EPA. It’s also crucial to inform any financial institutions, healthcare providers, or other parties that were given a copy of the original EPA. If the EPA were registered (e.g., with the OPG in the UK or for land transactions in some jurisdictions), you may need to register the revocation formally.

- What happens if an attorney dies or becomes incapable: If your appointed attorney dies, loses mental capacity, or becomes unwilling to act, the EPA may cease to be effective unless you have named alternate or successor attorneys. This is why appointing alternates is a best practice. If no alternates are called and the attorney cannot act, you must create a new EPA (if you still have capacity), or your family would face the court application process.

Frequently Asked Questions about Enduring Powers of Attorney

We often encounter common questions about enduring powers of attorney. Here, we address some of the most frequent inquiries to provide further clarity. For a broader understanding of how EPAs fit into your overall financial and legal planning, consider reviewing “The Basics of Estate Planning: What You Need to Know.”

Is an Enduring Power of Attorney the same as a Will?

No, an Enduring Power of Attorney (EPA) and a Last Will and Testament are distinct legal documents that serve different purposes:

- An EPA is effective during your lifetime. It grants authority to an attorney to make decisions on your behalf if you become mentally incapable. The attorney’s power ceases upon your death.

- A Will takes effect only after your death. It dictates how your assets will be distributed and who will be responsible for administering your estate (the executor).

While both are vital components of estate planning, they address different phases of your life. An EPA ensures your affairs are managed while you’re alive but unable to decide, whereas a Will ensures your wishes are carried out after you pass away.

How does an EPA differ from other types of powers of attorney?

The primary difference lies in its “enduring” nature.

- General Power of Attorney: This grants authority for a specific period or for specific tasks. It automatically becomes invalid if you lose mental capacity.

- Special Power of Attorney: This is for a single, defined transaction (e.g., selling a specific property). It also becomes invalid upon loss of capacity.

- Lasting Power of Attorney (LPA) in England: As discussed earlier, an LPA is the successor to the EPA in English law. It covers both property/financial affairs and health/welfare, offering a more comprehensive and modern framework than the original EPA, which was limited to financial matters. While the name is different, the core concept of enduring authority through incapacity remains.

The key takeaway is that an EPA (or its equivalent, like an LPA or Continuing POA) is specifically designed to remain effective after one loses mental capacity, providing continuous protection.

Does an EPA need to be registered with the government?

This varies significantly by jurisdiction:

- United Kingdom: EPAs created before October 1, 2007, must be registered with the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) when the donor begins to lose mental capacity for the attorney to legally act. New LPAs must also be registered with the OPG before they can be used.

- Canada (e.g., Ontario, Alberta, New Brunswick): Generally, there is no central government registry for powers of attorney. However, it is highly recommended to register your EPA with financial institutions, banks, and healthcare providers to ensure they recognize and accept it. If the EPA is involved in land transactions in some provinces, it may need to be registered with the land titles office.

- Australia (e.g., ACT, Queensland): Similar to Canada, EPAs typically do not need to be registered unless they are used for property transactions (e.g., land transfers), in which case the original document must be registered with the relevant land titles office.

Always check the specific requirements of your jurisdiction or consult with a legal professional to ensure compliance.

What are the implications of joint bank accounts compared to using an EPA for financial management?

While joint bank accounts might seem like an easy way to allow someone to manage your finances, they carry significant risks and offer less protection than an EPA:

- Ownership: Funds in a joint account are typically considered jointly owned. This means that if one account holder dies, the other usually becomes the sole owner (right of survivorship), potentially overriding your Will.

- Control & Risk: Any joint account holder can access and withdraw all funds, potentially leaving you vulnerable to financial abuse or mismanagement without recourse. An attorney, by contrast, has a fiduciary duty and is legally accountable.

- Creditors: The money in a joint account can be subject to claims from the creditors of any account holder.

- Accountability: As mentioned, an attorney under an EPA is legally bound to keep records and act in your best interest. A joint account holder has no such formal legal obligation.

For comprehensive and protected financial management, especially in anticipation of mental incapacity, an EPA is a far superior and safer tool than a joint bank account.

What happens if my attorney mismanages my affairs?

If an attorney mismanages your affairs, whether through negligence, abuse, or fraud, there are legal avenues for recourse:

- For the Donor (if capable): If you still have mental capacity, you can revoke the EPA, demand a full accounting of all transactions, and potentially pursue legal action for recovery of funds. For criminal acts like theft or fraud, reporting to the police is an option.

- For Concerned Third Parties (if donor is incapable): If the donor has lost capacity, concerned family members or friends can take action. This typically involves applying to a court (or relevant tribunal/public guardian office) to review the attorney’s accounts and conduct. This process, sometimes called a “passing of accounts,” can lead to the attorney’s removal and the appointment of a new attorney or a court-appointed guardian. In cases of suspected serious harm or financial risk, the Office of the Public Guardian and Trustee (or equivalent body in your jurisdiction) may investigate and initiate legal proceedings.

The legal system provides safeguards, but prevention through careful attorney selection and clear instructions in the EPA is always the best approach.

Conclusion

The enduring power of attorney is more than just a legal document; it is a profound expression of foresight and care. It offers the invaluable benefit of securing your wishes and protecting your assets and well-being, even when you can no longer articulate your decisions. By putting an EPA in place, you ensure that trusted individuals, chosen by you, can act on your behalf, avoiding the potential for stressful and costly court interventions that can arise from unforeseen incapacity.

We have explored the nuances of EPAs, from their historical context and evolution in English law to their varied applications across Canadian provinces. We’ve highlighted the critical importance of mental capacity in their creation, the careful selection of an attorney, and the significant responsibilities of the role. Understanding the difference between an EPA and other legal tools, like joint bank accounts, underscores the comprehensive protection that an EPA provides.

Proactive planning is key to peace of mind. By taking the time to understand and establish an enduring power of attorney, you are taking a vital step towards safeguarding your future and providing clarity and support for your loved ones. We strongly encourage you to consult with legal professionals in your jurisdiction. They can guide you through the process, ensure your document is legally sound, and tailor it to your specific needs, helping you craft a robust plan for whatever the future may hold. Don’t hesitate to reach out to discuss your estate planning needs and secure your legacy.